Other than tattoos, pigmentation disorders treatable with laser include nonspecific pigmentations, lentigo, freckle, melasma, Nevus of Ota and other disorders with Nevus of Ota like histological findings. What they have in common is the increased melanin pigments. Location of melanin pigments and whether melanocytes are increased or not may differ depending on the skin condition, and therefore need different applications of laser treatment.

With the development of early lasers for pigmentation disorders and the introduction of the idea of Selective Photothermolysis, tattoo treatment has started. As described in the previousarticle, tattoo treatment, before the development of laser, could not avoid a scar formation. Although laser treatment did not guarantee complete tattoo removal, it was one of the most important progresses in aesthetic treatment.

[Advertisement] Ultra Skin/Pastelle – Manufacturer: WONTECH(www.wtlaser.com)]

But there had been already good treatments like chemical peeling, electrosurgery and dermabrasion for skin conditions with skin color change or various pigmentation disorders except tattoo. In addition, because the early lasers for these problems were not very innovative, they had not been introduced to all clinics. For these reasons, procedures, such as chemical peeling, have coexisted with laser therapy and still remain as good treatment modalities.

Less and less doctors are learning chemical peeling, because laser is relatively easier to learn and provides considerably homogenous results. It should be reminded, however, that doctors with extensive knowledge and experience in chemical peeling sometimes bring better results than laser therapy.

Dermal melanocytosis, commonly represented by the Nevus of Ota, is similar to tattoo in terms of treatment. Cryotherapy, the standard treatment before laser, often left a scar. The development of laser should be considered as a ground breaking event, although not so perfect in every patient.

Generally, complete destruction methods of pigmented lesions start in early 1980sby using argon laser(Apfelberg DB The Argon Laser for cutaneouslesions. JAMA. 1981) and CO2 laser(Ratz JL. Carbon Dioxide Laser treatment of epidermal nevi. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1986 Jun; 12(6):567~70) Afterwords, dye Laser(PLDL-1 Laser, Pigmented Lesion DyeLaser-Candela co. 510nm, pulse duration of 300 +/- 50nano-seconds.), Q-switched Ruby Laser, Q-switched Alexadrite Laser and Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser were introduced in late 1980s for relatively selective destruction of melanin pigments. Among them, Q-switched Ruby Laser and Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser were already in use in ophthalmology from 70s and 80s. They had been introduced in dermatologic field with basic studies supporting the possibility of selective damage of skin pigment.

From mid-2000s, the idea of Fractional Photothermolysis has been introduced sporadically to various lasers. With IPL devices gaining popularity again between late 1990s and early 2000s, IPL has been used in clinics which do not have laser systems or for patients who want less down time rather than efficacy. With recent introduction of Long Pulse Alexandrite and Long Pulse Nd:YAG, new treatments have been tried to reduce the down time while maintaining the therapeutic effect.

Pigmentation disorders are mostly aesthetic acquired disorder but some of them are congenital. Most cases are pure aesthetic skin conditions developed in adulthood by the influence of UV rays. Incidence of pigmentation disorders is very high, so dermatologists usually treat these lesions every day. Because the aesthetic treatments cannot be considered as important subjects in medicine, the development of standard therapies is not easy. The need for trained and experienced dermatologists for differentiation and diagnosis of various subtle skin changes also plays as a barrier for providing the best laser treatment.

1. Treatment of the Nevus of Ota

Q-switched Ruby Laser, Alexandrite or Nd:YAG laser, developed in the US and Europe, showed good results for the treatment of the Nevus of Ota (Geronemus RG. Q-switched Ruby Laser therapy of nevus of Ota. Arch Dermatol 1992; 128: 1618~22). However studies on objective therapeutic effect were conducted mostly in Asians because this disease is more common in Asians. (Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Otawith the Q-switched Ruby Laser. N Engl J Med 1994;331: 1745~50).

Dermal melanocytosis and acquired bilateral Nevus of Ota-like macule (ABNOM), which have histological findings similar to the Nevus of Ota, were reported to have similar effects when treated with the same treatment principles for the Nevus of Ota. Despite similar therapeutic prognosis, the procedure has not become common procedures due to the lack of cases for doctors to accumulate sufficient therapeutic experience and the difficulty in continuing the procedure more than 5 times.

I was recently consulted on the treatment of a 1-year-old baby with aberrant mongolian spot on the wrist, for which I gave an information about a paper published in Japan (Shirakawa M, Ozawa T, Ohasi N,Ishii M, Harada T. Comparison of regional efficacy and complications in the treatment of aberrant mongolian spots with the Q-switched Ruby Laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010 Jun; 12(3): 138~42). The baby’s father was a Korean but because the mother was a Japanese, the baby could receive a consultation from the doctor who published the paper. Due to the expensive medical expenses, however, the patient returned to a well-known university hospital in Korea, where they were informed that the hospital was not capable of providing the treatment and none of the other hospitals in Korea would, either. I was perplexed when the patient visited me again. After asking around to find a Korean hospital equipped with the facility for general anesthesia and Q-switched laser in the same operating room, I could find an experienced hospital and referred the baby.

This story is a good example implying that doctors should not make a hasty conclusion that ‘a certain treatment that I can’t do is also not available by other doctors.’ What’s more surprising is that aberrant mongolian spot is not uncommon in Korea and there are doctors with ample experience with it. This also shows how there is lack of communication among laser surgeons in Korea.

Korea tend to introduce various lasers more rapidly than in Japan – due to conservative permission of laser import by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan For this reason, some Japanese doctors visited Korea to observe various laser treatments in 1990s. This suggests the importance of the efforts to share specific knowledge on existing laser therapies for individual diseases, in addition to the information exchange for new devices.

2. Skin changes with excess melanin pigments

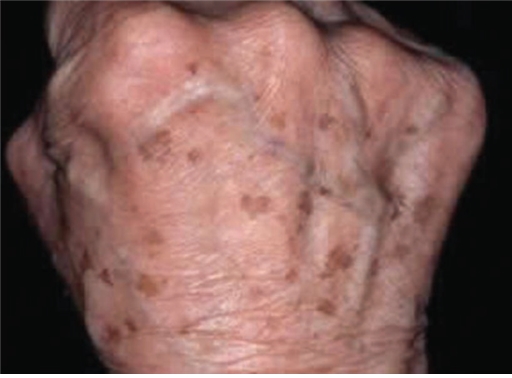

This refers to the skin condition categorized as congenital brown spots, lentigines (Fig 1), freckles and nonspecific pigmentations, which can be easily treated with 510nm and 532nm lasers but often recurred. As described earlier, electrosurgery or chemical peeling is also available other than laser, and IPL, if used properly, may also provide a good effect. Compared to acquired lesions, Cafe au lait macule and nevus spilus do not respond to laser therapy very well.

Fig 1. Lentigos

3. Melasma

A lot of dermatologists consider melasma as a disease or skin condition untreatable by laser, based on a very significant paper which reported no effectiveness from Q-switched Laser (Taylor CR, Anderson RR. Ineffective treatment of refractory melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation by Q-switched Ruby Laser. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994 Sep; 20(9): 592~7). If my memory serves me right, however, Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser with very low fluence was used for melasma treatment at Kim Yangje Dermatology Clinic, Pusan, Korea, in mid 1990s already. More than 15 years have passed and many studies in Korea have reported the results of this concept recently. These days many Korean dermatologists are doing researches about melasma treatment. It is also true that dermatologists from other countries often mention Korean papers on melasma treatment during their lecture in international seminars.

Despite the lack of definite pathophysiology, there is a general agreement that melasma is associated with increased melanin in the epidermis and angioplasia in the dermis. Contrary to the study by Rox Anderson (1994), it may be possible that laser systems with a predictable treatment result at some level will be developed in the near future. Korean investigators are expected to play an active role in this area.

4. Conclusion

Beckers nevus, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, nevocellular nevi and blue nevus are also being considered as the target of various laser therapy. Pigmentation disorders for laser therapy are the most frequently encountered lesions in dermatology, but the thought that these lesions are easy to treat led to the lack of communication between doctors, contributing to the slow development. Being a very important laser therapy among Asians, however, they deserve continuous interests in the future. I would like to end this article on laser therapy for pigmentation disorders with the introduction of 2 papers worth reading.

Papers on pigmentation disorders

1. Polder KD, Landau JM, Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Goldberg LH, Friedman PM, Bruce S. Laser Eradication of Pigmented Lesions: A Review. Dermatol Surg. 2011 Apr 14.

2. Kang HY, Ortonne JP. What should be considered in treatment of melasma. Ann Dermatol. 2010 Nov; 22(4): 373~8.

-To be continued-

▶ Previous Artlcle : #6. Development of Lasers for Pigmentation Disorders I

▶ Next Artlcle : #8. Development of Ablative Laser Resurfacing